Billion Dollar Question

How Connecticut School Districts Plan to Spend COVID-Relief Funds

.jpg?width=2000&height=600&name=ESSER-Funding-Report-Hero%20(1).jpg)

By Bella DiMarco, Amber Martin, Ashley Robles, and Phyllis W. Jordan

Across Connecticut, the Covid pandemic has left an indelible stamp on student learning and mental health. Standardized testing reveals many students have fallen months behind academically. Behavioral concerns and stubbornly high absenteeism rates speak to the anxiety and depression still afflicting many students. To address the catastrophic impact of Covid, Congress approved three waves of emergency funding for K-12 public schools, providing a total of $1.7 billion for Connecticut. With local and regional education agencies set to receive at least 90 percent of the federal windfall, it’s instructive to know how they plan to spend it.

To find that answer, the School and State Finance Project, FutureEd, and ConnCAN tapped a state database detailing how much each Connecticut school district, charter school organization, and regional education office has requested in American Rescue Plan funds. As of July 2022, the state has approved requests from 193 of its 204 education agencies, representing $887 million of the $1.1 billion allotted to state and local agencies through the federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Fund, known as ESSER III.

We broke down the spending proposals into five broad categories and drilled down further on specific priorities. In some instances, we included a proposal in two categories: Salaries for tutors, for instance, were counted in both the staffing and academic recovery columns. We also examined spending trends based on district economic conditions and geographic settings. When possible, we compared Connecticut’s plans to national trends that FutureEd has identified in its analysis of more than 5,000 local spending plans compiled by the data-services firm Burbio, a sample that represents three-quarters of students nationwide.

While the Connecticut State Department of Education has approved much of the proposed local spending, school districts and charter organizations have spent only 11 percent of that money as of July 2022. Schools have until late 2024 to spend the ESSER funding, and their plans spread the expenditures across a three-year period. What’s more, some districts are having trouble spending the funds they budgeted, either because they can’t find the needed staff or they face supply-chain challenges on facilities projects. Recognizing this, the U.S. Department of Education is offering extensions for local agencies that need more time to complete contracts.

Our analysis found the following:

- Staffing: School staffing emerges as the top priority statewide, with every district and charter school in the Connecticut database pledging to spend on hiring, rewarding, or training staff members. The state’s overall level of investment in staffing outstrips that found in the Burbio national sample.

- Academic Recovery: Addressing learning loss is a requirement under the American Rescue Plan and takes many forms in Connecticut’s localities, with investments in instructional materials and summer learning most common. The share of statewide spending on this category, however, is lower than the share dedicated to learning loss nationwide.

- Mental and Physical Health: Student mental and physical health are key concerns, with two-thirds of the state’s districts panning to invest in those areas. Family engagement is a key strategy, which Connecticut educators are far more likely to embrace than those nationwide.

- Special Populations: While the ESSER aid is targeted at school districts with the highest needs, some communities set aside additional funding for special populations, particularly students with disabilities and English language learners.

- Facilities and Operations: Spending on facilities and operations is expected across Connecticut, with nearly three-quarters of local education agencies committing to repairs, construction projects, and transportation needs. About half the projects involve improving air quality and ventilation, similar to national rates.

The trends suggest Connecticut schools are committed to priorities that can make a difference for student learning. The challenge ahead is to ensure localities are spending the federal aid as planned and contemplating how to continue key initiatives after the money runs out.

Staffing

The emergence of staffing as Connecticut’s top priority for Covid-relief spending, comprising nearly $480 million of the $887 million approved by the state Department of Education, reflects the reality that personnel costs typically account for the lion’s share of school expenses. But a deep dive into the data shows that much of the money is going to pandemic-specific initiatives such as reducing class sizes and adding reading and math specialists, tutors, and summer learning staff, as well as benefits for these workers.

Some districts are creating new positions: Bethel School District, for example, is paying for a full-time math specialist to support students at its middle school. Columbia School District, which operates a single school, added two full-time positions to create smaller class sizes and more instructional support at the middle school level.

Ansonia School District, an Alliance District, is hiring a manager for its new high school robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) lab. All told, 71 percent of Connecticut’s local education agencies are adding teachers and interventionists, compared to 59 percent in the Burbio's national database.

In contrast, a lower percentage of Connecticut districts plan to invest in recruitment and retention efforts than those nationally. About 5 percent of the state’s districts are offering bonuses, compared to 11 percent nationwide. Given the dire need for substitute teachers, some districts developed creative solutions to ensure coverage would be available for teachers out sick due to Covid, Woodstock School District hired two substitutes to work a full-time, three-year term at each of the district’s two school buildings.

The Connecticut districts with the highest rates of economically disadvantaged students are putting about half of their Covid-relief allotment toward staffing, while the most affluent localities are using about two-thirds of their funds for that purpose. For districts investing in staffing, spending on teachers remained the top priority in terms of money allotted at almost every economic level and across all locales. In cities, the second-highest spending priority was providing benefits, while suburban districts prioritized bringing in psychologists and mental health professionals, towns focused on hiring summer staff, and rural districts on hiring tutoring staff.

Given the one-time nature of ESSER funds, Connecticut’s investments in recurring staffing costs raise questions about how these positions will be funded when federal aid is no longer available. A more sustainable approach would be to spend the funds on professional development for existing staff members. Nearly half of districts and charters in Connecticut have taken this approach. East Windsor School District, for instance, is launching an extensive staff development program that includes an executive coach for district administrators, while New Britain is hiring 20 instructional coaches to work with teachers in pre-K through high school. Coventry School District is training social workers and psychologists to conduct home visits. Thirty-six districts are investing in training for staff members on how to provide more equitable outcomes for disadvantaged students.

Academic Recovery

From March to June 2020, all Connecticut schools shifted from in-person instruction to distance learning, leading to significant challenges in educating students such as higher absenteeism rates, lower enrollment, and reduced academic attainment. While the majority of districts returned to in-person classes at the start of the 2020-21 academic year, gaps in instructional time persisted. To help students recover, the American Rescue Plan mandates local education agencies allocate at least 20 percent of their ESSER funds to address learning loss. Connecticut reinforced this priority in its plan for spending the $110 million reserved for the state education agency, and the state requires districts to provide information on the planned uses of stimulus funds.

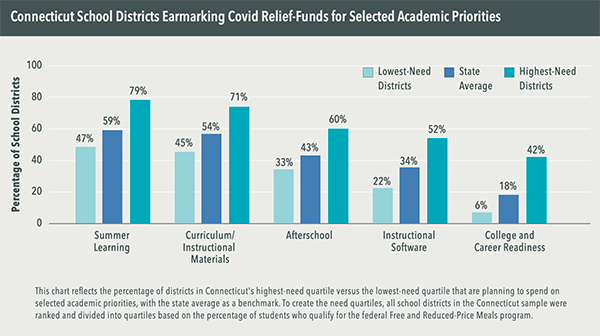

All told, Connecticut districts and charters earmarked $229 million to target learning loss, with about $61 million going toward curriculum and instructional materials, $50 million for summer learning programs, and more than $40 million each for afterschool programs and tutoring. About 59 percent of districts plan to use their federal aid on summer-learning programs and 54 percent on curriculum and materials.

This compares to 52 percent of districts in the Burbio national sample that are devoting funds to summer learning and 36 percent for curriculum and materials. Overall, academic recovery accounts for about a quarter of planned expenditures nationally; in Connecticut the total dollar figures fall below spending on staffing and on facilities and operations.

Districts’ responses to learning loss vary widely. In Waterbury, the school district is paying 200 teachers and 30 other staff members to provide summer learning for students over the next two summers. The Derby School District is paying tutors to work 15 hours a week in two elementary schools. Achievement First Bridgeport and Amistad Academy are funding an inter-district program that partners with local foundations to provide small- group or one-on-one tutoring every day. West Hartford is leasing a storefront to operate a bookstore for students to acquire necessary job and socialization skills.

Because the federal aid is allocated based on the Title I formula for supporting schools with higher needs, the districts with the highest rates of economically disadvantaged students have more money to spend. Hence, a larger proportion of the highest-needs districts are spending on such priorities as college and career readiness, summer programming, curriculum and materials, instructional software, and afterschool programming. Even so, the more affluent districts dedicate a bigger share of their limited dollars than other districts to afterschool and summer programming, and to curriculum and instructional materials. Some districts are not planning to invest their ESSER funds in evidence-based interventions but are instead counting personnel expenditures toward meeting the federal 20 percent threshold for addressing learning loss.

Mental & Physical Health

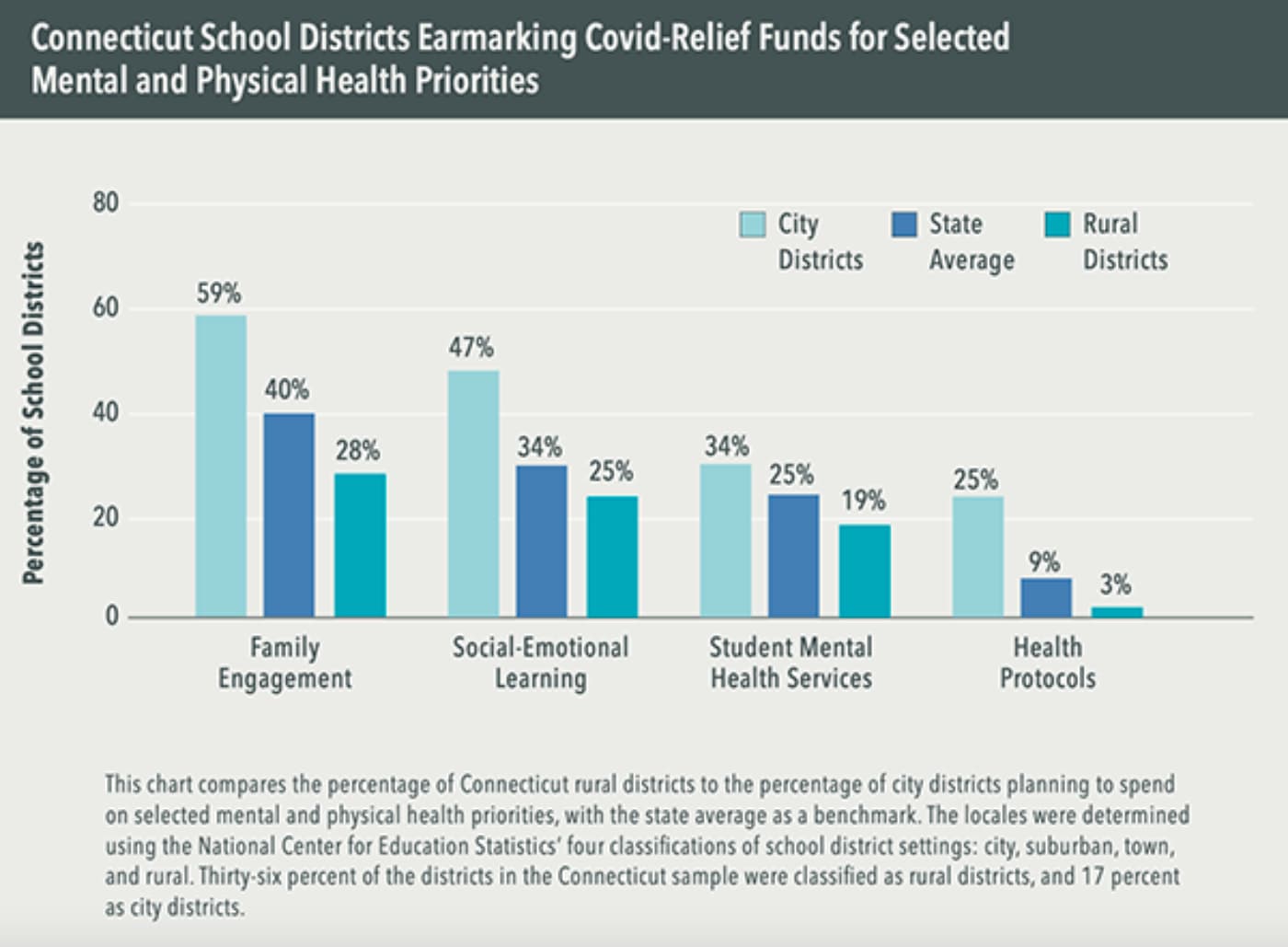

n response to the isolation and trauma students experienced during the pandemic, more than two-thirds of Connecticut districts are investing a total of $71 million in mental health support, with much of the money focused on behavioral health priorities such as social- emotional learning and wraparound services. Nearly half of the districts earmarked money to bring mental health professionals into schools—a $59 million investment that is counted under staffing in this analysis. Family engagement, which covers everything from family nights to support programs, is a top priority in Connecticut, with 40 percent of districts pursuing this option — far greater than the 21 percent nationally. More than a third of districts also plan to spend on social-emotional learning, while a quarter of districts are earmarking money for student mental health services, which is similar to national trends. Many districts are pursuing a combination of supports.

The Ledyard School District, for example, is designating money to provide middle school counseling for social, emotional, and academic challenges, as well as mental health diagnoses, individual and family therapy sessions, and on-call support. The district also plans to provide professional development opportunities for teachers and parent education workshops to help address student needs. The New Britain School District is investing in home visits, during which teachers or staff members periodically check in on students and families. The district plans to provide extra pay for 200 staff members who will each focus on six students and their families.

The Connecticut districts with the highest rates of economically disadvantaged students are the most likely to spend on mental and physical health. Eighty-five percent of districts in the highest quartile plan to spend on such priorities. Family engagement is also a top priority, with 71 percent of high-need districts planning to invest in that strategy. Half of the districts plan to spend on social-emotional learning, and a third on student mental health supports.

There are stark differences in spending on mental and physical health among city and rural districts in Connecticut. Eighty-one While the Connecticut State Department of Education has approved much of the proposed local spending, school districts and percent of city districts and charters plan to invest in mental and physical health, spending an average of $379 per student. That compares to 59 percent of rural districts, which are planning to spend $90 per pupil. Family engagement, social- emotional learning, and student mental health services remain the top priorities across all locales.

City districts are twice as likely to spend on family engagement as their rural counterparts (59 percent compared to 28 percent) and nearly twice as likely to spend on social-emotional learning (47 percent compared to 25 percent.) One city charter school, Booker T. Washington Academy in New Haven, where 80 percent of the students qualify for the federal Free and Reduced-Price Meals program, is building out a system of social-emotional and mental health support. This would include establishing a referral system to connect students to mental health resources, instituting trauma- informed practices in the classroom, and providing targeted intervention for those most in need.

Special Populations

The Covid-19 pandemic hit Connecticut’s most underserved students disproportionately hard, including racial and ethnic minorities and those from economically disadvantaged families. While wealthier families were able to hire tutors, participate in small- scale learning pods, or, in some cases, send their kids to private schools, many children from economically disadvantaged families lacked these opportunities and went without consistent schooling for the better part of two years. As a result, research has shown proficiency and growth rates for Connecticut’s high-needs students have declined compared to pre-pandemic levels. During remote learning, other student groups—particularly those with disabilities and English language learners—were often unable to access the support their schools typically provide.

Since the ESSER funding flows through the federal Title I formula, much of the ESSER aid supports students most in need of academic, social-emotional, and behavioral interventions. Some districts, though, are allocating money specifically for some of these special populations, totaling $62 million statewide. Thirty percent of districts in Connecticut requested money to support students with disabilities, more than twice the share of districts nationally. And nearly one in five districts is planning to set aside money for English language learners. A handful of districts also highlighted specific programs and support for economically disadvantaged children and students of color.

Some districts are dedicating special summer, afterschool, or tutoring resources to these high-risk groups, while others are hiring special education teachers or language instructors. Clinton School District, for example, plans to host family nights specifically to engage and support economically disadvantaged families and families of students who are English learners, receiving special education services, or in need of academic and behavioral intervention. New London School District plans to hire a bilingual supervisor to improve family engagement. Groton School District is hiring tutors to address learning loss, as well as behavioral and social-emotional challenges, specifically for economically disadvantaged students, children with disabilities, English learners, and racial and ethnic minorities. And Manchester is setting aside part of its allotment for on-site mental health services at each of its 13 buildings specifically for homeless and displaced youth.

The percentage of districts planning to spend on high- risk students is consistent across Connecticut, although it differs by geographic setting. Suburban districts are the most likely to request funding specifically for students with disabilities (39 percent), while city districts are the most likely to spend on English language learners (31 percent).

Facilities & Operations

While academic programs and staffing dominate Connecticut’s plans for spending federal Covid-relief dollars, as much as $238 million in 139 districts will go toward capital projects and operational spending on such needs as transportation and pandemic protections.

Upgrades of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems constitute the largest share of facilities spending. Meriden School District, for instance, is adding air conditioning to four elementary schools.

Danbury is conducting a comprehensive overhaul of its HVAC systems, including boilers, air vents, air conditioning, filtration, and other components. While these air quality initiatives are important for stopping the spread of the coronavirus, they can also have benefits for student achievement by providing cleaner, more comfortable environments for learning.

Other capital projects involve fixing leaky roofs, improving bathrooms, or removing lead and asbestos hazards. The emphasis on facilities and operations mirrors what’s happening on the national level, where nearly a quarter of the designated ESSER III spending is earmarked for such priorities.

The districts serving the highest rates of economically disadvantages students are spending considerably more on facilities and operations than their wealthier counterparts, for obvious reasons.

Due to ESSER they have more to spend, and, in many cases, have far more need, given aging facilities and years of funding shortfalls.

In the poorest quartile of districts, about 81 percent of the districts are spending on facilities and operations, earmarking a total of around $197 million. In the most affluent quartile, by contrast, 63 percent are spending on facilities and operations, earmarking around $9.5 million.

The surge in school facilities projects coincides with an investigation by the FBI of a former Connecticut official’s handling of school construction bids and contracts. While the state legislature recently sought to tighten the school-contracting process and increase accountability, the involvement of federal authorities could complicate districts’ efforts to spend ESSER dollars before the late 2024 deadline. Already, districts are struggling with supply chain delays and labor shortages. The U.S. Department of Education, recognizing that these issues affect schools nationwide, has agreed to consider extensions for certain projects.

Conclusion

Connecticut’s school districts and charter schools have another year and a half to spend nearly $1 billion allotted to them through the American Rescue Plan, on top of the half billion dollars from two earlier rounds of federal Covid-relief aid.

The unprecedented infusion of money offers an opportunity to address persistent achievement gaps, strengthen local education infrastructure, and introduce new support for students. But it also brings challenges, not the least of which is finding ways to sustain successful programs after the extra funding expires. It is essential that districts track which interventions improve student engagement and achievement in Connecticut schools, so education leaders can invest resources in what works best for students.